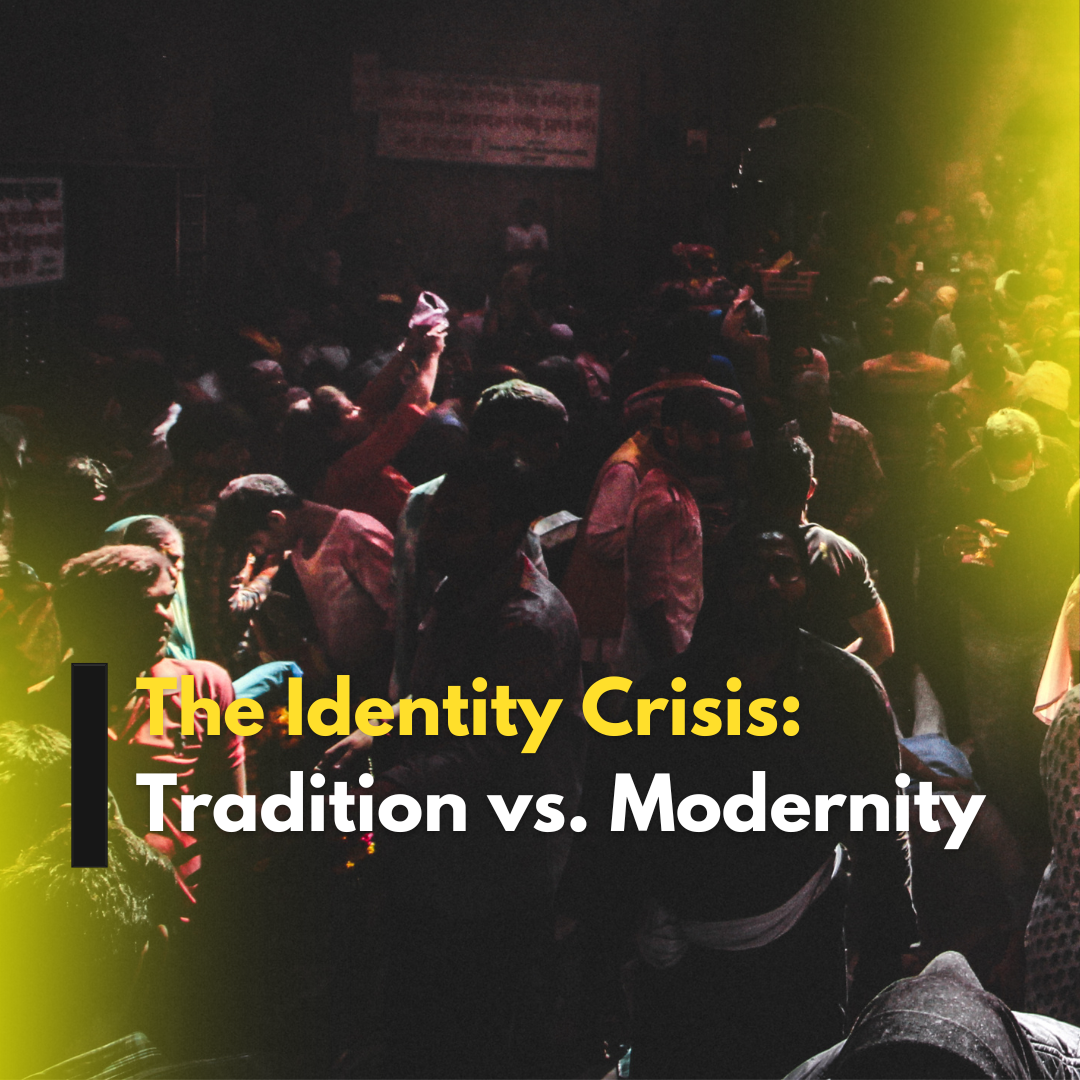

India's Identity Crisis: Tradition vs Modernity — The Twice-Born,” a new memoir by Aatish Taseer, is troubled by a single plaintive question: Does a city steeped in tradition have a future in modern India? The setting is Benares, the spiritual capital of Hinduism, where more than five million pilgrims flock each year to worship, bathe, and burn their dead. Dying while in Benares, it is said, will release a Hindu from the cycle of reincarnation, and Taseer discovers an industry of death that’s alive and well in the city. He describes corpses that “sizzled away on funeral pyres,” as dinghies drifted on the Ganges amid smoke and marigolds.

Taseer, to be clear, has not come to Benares to die. He’s in his thirties for most of the memoir, and, anyway, he’s not religious. His pilgrimage is secular; he seeks to filter the contradictions of present-day India through his life story. In the process, “The Twice-Born” becomes a moving, if maundering, riff on what it means to be modern. For Taseer, Benares incarnates a curious quality of modernity: the city makes anthropologists of the devout and believers of the skeptical. The book’s charm resides in the way the author orbits this tension between faith and rationality. He yearns to make sense of how “the laws of reason and the laws of magic . . . reached an easy harmony” in contemporary India.

Taseer attempts to focus the book on his interactions with Brahmins, Hinduism’s priestly caste. (They are the twice-born of the memoir’s title, because they are considered to be born a second time upon their scholarly initiation.) But Taseer is foremost a wanderer, and the roving form of the book echoes his penchant for circularity. He writes as though Benares, in all its many dimensions, can be apprehended only through overlapping, fractal perspectives, one of which is his own.

Taseer’s relationship to himself is distinctly spectatorial; he cannot stop looking at himself looking at himself. “I saw everything as an Anglicized Indian watching an imaginary European or American visitor watch India,” he writes. “I wished I had a more direct relationship with my country. But any attempt to do so only made the self-observing selves multiply.” This double vision is a product of Taseer’s hybrid upbringing. He was born in England, in 1980, and raised in India. His father was the Pakistani politician Salman Taseer, who was murdered by his own bodyguard; his mother was an Indian journalist. These facts of life, coupled with extended stints in the United States, have steered him toward itinerancy, forever between cultures. V. S. Naipaul, Taseer’s former mentor, is repeatedly mentioned in the book, and it is written in his exilic spirit.

In order to fashion a more authentic—or at least a less vexed—relationship to India, Taseer takes up Sanskrit. He admits that “my wish to learn Sanskrit was an attempt to deal intellectually with a country whose reality perturbed me,” but the language bequeaths him a vast literary inheritance. After roughly a decade of study, he begins to pore over Shakuntala, the most famous Sanskrit play, and to mine Indian literature for his own literary pursuits. This section of the memoir doubles as a brief lesson in history and literature. In describing how the British philologist William Jones “discovered” Sanskrit and noticed its affinity with Greek, Taseer nudges the reader toward his main thesis: history inheres in modernity. India’s future, in other words, lies in the recovery of what was forgotten or suppressed during the colonial encounter: its literary, cultural, and intellectual past.

History, however, is distinct from tradition. The latter is dangerously pliable; anything can be justified in its name. Taseer realizes this near the end of his stay in Benares, when he absent-mindedly brings his driver along to a dinner hosted by a Brahmin family. As the dinner ends, a silence falls over the table. The host whispers to Taseer that, although the family has generously allowed the driver to eat with them, he must wash his own plate; his saliva has “polluted” the silverware. Taseer cannot bring himself to deliver the instruction, but the driver, once told by the host, is surprisingly unfazed. “You are like gods to me,” he replies

Episodes like this slowly disenchant Taseer. His reverence for the literary and spiritual traditions that the Brahmins embody is diminished by his growing awareness of the privileges they continue to wield, even in a modern democracy. “The spread of modernity in India threatened caste but also made the need to assert it more vehement,” he writes. “Brahmins continued to exert an outsize influence over intellectual life; the armed forces were still dominated by the martial castes; a majority of the rich businessmen and industrialists still belonged to the mercantile castes; and the lower castes still did the most wretched work.”

In these lines, Taseer adopts a historian’s tone, and he is fond of braiding his quest for knowledge with one-off quotes from scholars, writers, and experts. References to Dostoyevsky, T. S. Eliot, Octavio Paz, Mark Twain, and contemporary thinkers, such as the Indologist Sheldon Pollock, flit in and out of the narrative, pell-mell, but they offer an international precedent for India’s uneasy encounter with modernity. Nietzsche is not cited in Taseer’s book, but he would not have been out of place. In fact, in “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life,” Nietzsche neatly sums up Taseer’s evolving relationship to the Brahmins—and to modernity itself. To be modern, for Nietzsche, is to radically forget the past. But he also warns, “this very life that has to forget must also at times be able to stop forgetting; then it will become clear how illegitimate the existence of something, of a privilege, a caste, or a dynasty actually is, and how much it deserves to be destroyed.”

Benares, it turns out, possesses a naturally levelling force. The city is suffused with a form of darkness that locals call tamas, which “is inseparable from the chthonic energy of Shiva, the city’s presiding deity, and the god of creative dissolution,” Taseer writes. “The city deals in equal measures of light and shade. There is dirt and squalor, death and disease; but there is also the transcendent spectacle of the river, and the utter beauty of people lost in meditation, waist-deep in water.” The tamasic mood was elegantly characterized by one of the city’s best-known residents, the Swiss artist Alice Boner, who lived there from 1935 to 1978. Taseer stays in Boner’s former home, and the memoir is happily leavened with excerpts from her diary. “The terror of the utter loneliness of death,” she wrote, in 1954, “had given place to the feeling of the great community of death, the only real community, the only condition in which all differences are obliterated and all are one, merged into the same substance.”

“Alice came to be a friend across time,” Taseer writes, though the two writers arrive at vastly different conclusions following their stays in Benares. For Boner, the city annihilates the individual, while Taseer views it as a place to conjure a sense of self. His is a search for identity and narratable experience—indeed, for him the two are indistinguishable. But, by the memoir’s close, he has only circled the sense of clarity that he sought. Though he came to Benares to walk, talk, listen, and write, the tamasic charge of the city has not unshackled him from the paradigm of personal identity—of his desire, above all, to look inward. He is condemned, he muses, to live life as a perpetual drifter, never at home anywhere, the perfect chronicler of a vagabond modernity. And so he decides to uproot himself once more and move back to New York. The reason he gives is telling: even in Benares, “people would always be able to place me at glance—as English-speaking, as Muslim, as part of the class of interpreters.” The self-observing selves, it seems, have returned. The memoir thus ends where it begins: Taseer seeing himself seeing, with his eyes closed.

Article originally written by Shaj Mathew

The information contained in this article was sourced from Indian Currents

Link to original article: https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-twice-born-a-searching-memoir-about-indias-identity-crisis

Notes: apart from title change, the article has remained the same

-------------------------------